Fear of Failure: Vietnamese Workers in Japan Strangled by Expectations

The Struggle of Vietnamese Workers in Japan

Nhat Tuan, a 28-year-old from Bac Ninh Province, has spent five years in Japan without ever returning to Vietnam. His dream of a life-changing journey has not materialized as he had hoped. In 2020, he left a factory job that paid VND10 million (around $380) per month and borrowed VND300 million from his parents to move to Gifu Prefecture for agricultural work. At the time, recruiters promised him a monthly income of VND30-40 million, excluding overtime pay. He believed that within two years, he could repay his debt and save enough to start a business back home.

Reality proved far different. For the first three years as a technical intern, Tuan earned only 90,000–110,000 yen ($570–$640), which is roughly VND15–17 million. Instead of tending bonsai trees, as his contract stated, he found himself doing tasks like repairing roofs, clearing sewers, and shoveling snow. Even in winter, when water froze, he spent his days wading through icy ponds to harvest lotus roots or trimming cactus spines by hand.

Despite the harsh conditions, Tuan did not dare quit because of the debt he carried. It wasn’t until the end of his second year that he finally repaid the loan. At that point, he considered returning home but hesitated. Two years of hard labor had brought him back to the starting line—no savings, no career, and no clear explanation for his family.

He decided to stay for a fourth year to qualify for the "Specified skilled worker" visa, which increased his salary to around 170,000 yen. However, this coincided with a sharp decline in the value of the Japanese yen and rising inflation. Tuan now spends 50,000 yen on rent and food, and 20,000 yen on insurance and taxes. After covering other living expenses, he is left with only VND12–14 million each month. Most of this goes back to his family, while he keeps only a small amount for emergencies.

The greatest pressure on Tuan comes not from the physical labor but from the fear of "losing face." Calls from home asking, “When will you build a house?” or “How much money are you sending back?” have become a heavy burden. He also worries about what he would do if he returned to Vietnam. His agricultural experience in Japan does not translate well to higher wages back home, and returning to factory work would feel like going back to square one.

“I don’t have the courage to gamble on my future again,” he says.

Tuan is not alone in this anxiety. Huu Minh, 32, from Hai Duong Province, moved to Japan in mid-2023 with the goal of earning enough to rebuild his family home. Despite cutting his expenses to the bone, he manages to send home VND17 million a month. If he returns now, his savings would be around VND300–400 million, which would barely cover the cost of building the house. He fears falling into the same trap as many others who return to open businesses like bubble tea shops or noodle stalls, only to fail due to lack of experience.

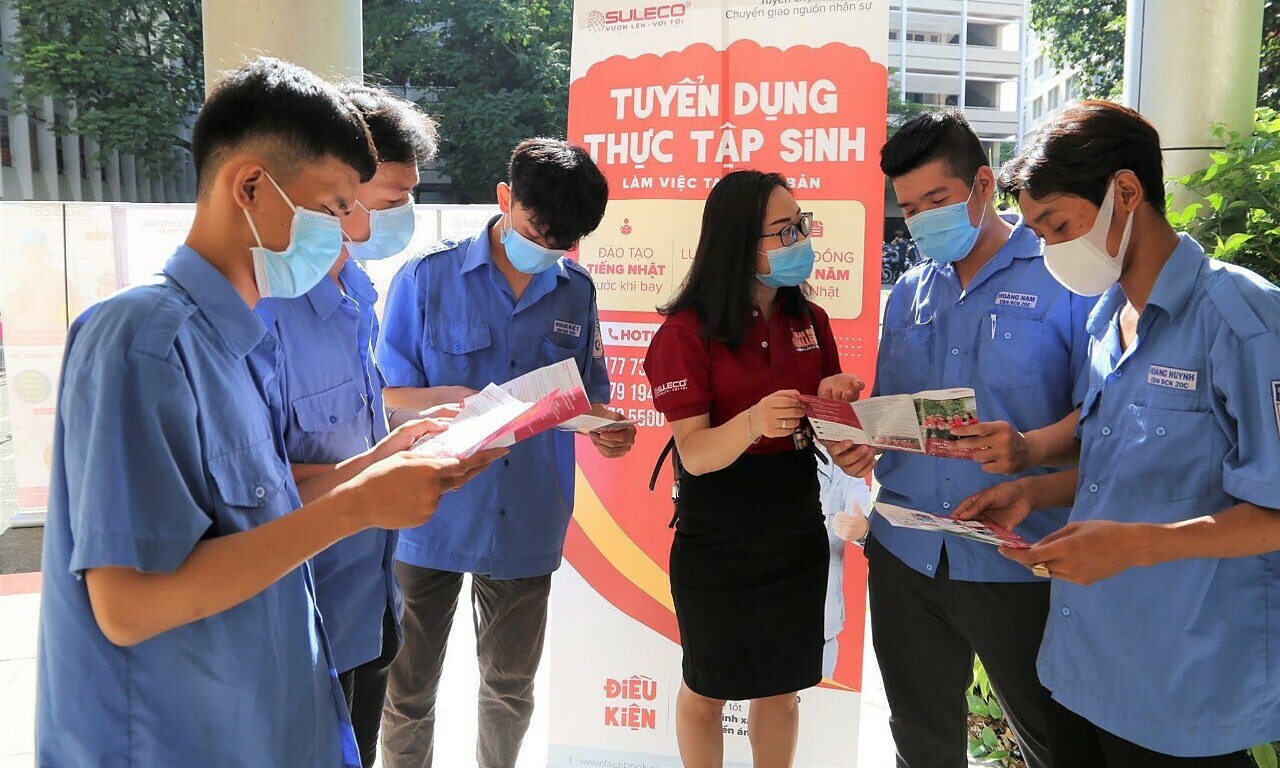

As of 2024, Vietnam had over 158,000 citizens working abroad, with Japan being the top destination. With an average wage of around 180,000 yen a month, Japan is still seen as a prime opportunity for wealth-building. However, behind the numbers lie significant challenges.

According to the International Labour Organization, the average cost for a Vietnamese worker to go to Japan was VND192 million, among the highest in the region. Studies by Japanese immigration authorities show that over 50% of Vietnamese interns have debt burdens equivalent to more than two years of minimum wages. By mid-2025, the weakening yen caused remittances to drop by 10–20%, forcing many to stay longer than planned.

Truong Nhat Tai, deputy director of Hasu Asia, explains that the reluctance to return stems from three main factors: a lack of transferable skills, the illusion of high income, and the rapid depletion of savings upon returning to Vietnam.

Tai emphasizes the importance of career orientation before workers leave. He believes that workers should be guided toward jobs that match their abilities and the economic reality of their hometowns. For example, if a worker’s family has farmlands, they should be trained for agricultural jobs rather than food processing or electronics assembly.

His company tailors training programs to practical needs, ensuring that workers can adopt high-tech agricultural models or quality manufacturing upon returning. The goal is to help them feel prepared and confident when they come home. “When they are sufficiently prepared, they won’t feel lost when they return to Vietnam,” he says.

Posting Komentar